I've been doing a lot of bird watching lately. Well, bird watching and bird listening. I really like the free Merlin app from Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

For years, I used Merlin as a database of local birds to peruse, comparing what I saw to the photos.

I knew it had an automatic sound ID feature, but I refused to use it. Isn't using AI for birdwatching cheating?

I also assumed it needed Internet access to work, and usually out West when I hear an interesting bird I'm in some remote campground or dispersed camping on National Forest or BLM land and can't even get texts. I recognize a few bird calls, like crows (“caw”) and chickadees (“chicka dee dee dee”).

We went on a bird walk with a lovely volunteer, a real birder, who used the sound ID in the app in addition to being familiar with the birds in the local area. We saw like twenty kestrels on that walk near Mono Lake. I'd never identified a kestrel before. That's the magic of learning from other people's experience.

A couple weeks later, I was at a marina. Birds were twittering and flying from tree to tree. A night heron was cleaning a wing, sitting in a tree.

I didn't know what the flock of small birds was. I opened Merlin and pressed the Sound ID button. What the heck, I thought. Let's see.

A few seconds later, “Lesser Goldfinch” popped up on the screen. I clicked into the listing to read the description. I gazed more closely at the birds. Yes, I could see the yellow feathers! I was excited to learn something new.

I don't travel or hike with binoculars, by the way. Too heavy and breakable. So my birding is often limited to who flies quite close to me.

Camping up near the ancient bristlecone pine forest to escape the heat wave in gorgeous stillness, I was quite confused by the small birds flocking near our campsite, hopping around in the juniper trees every morning. I saw flashes of stripy black and white, but at other times the birds looked smooth, without a pattern. Were they nuthatches? I didn't see them walking upside down around the tree trunks, a classic nuthatch behavior. The black and white pattern didn't look like a chickadee – too many stripes. Just as I had decided, these are definitely not chickadees, I heard from behind me, “chicka dee dee. Chick a dee dee dee.”

Aaaaaaaaaaaa.

Dave asked me if something was bothering me, perhaps guessing some work or people thing was going on as I squinted at my phone, frustrated.

“No, it's just the birds,” I replied, a bit guilty. “I can't tell what these are! They don't match any bird in the list.”

“Why don't you try the sound ID, maybe make a recording so you can check it later?” Dave suggested.

I sighed, and agreed.

Even with zero cell signal, my app started recording and then identifying! The first bird to pop up was the Mountain Chickadee which I had heard. Then, White-breasted Nuthatch! Dave and I looked around and saw the nuthatch, making its way around the trunk of the tree behind us. The other small birds were gone, transient, still hard to identify.

The description for Mountain Chickadee included, “Often in flocks with nuthatches and kinglets.” Well, we had just seen the nuthatches. I checked the entries for kinglets, a bird I was unfamiliar with. The kinglet has a smooth, olive-green body with darker wings. “Often forages quite low to the ground, sometimes joining mixed flocks of other songbirds. Energetic, moving quickly, and flicking its wings.”

Maybe that was the smooth-colored birds. And then there must have been another black-and-white type. Not a chickadee. I looked for black-and-white stripy birds, now that I was free from the restriction that they also had to look like kinglets, and found two warblers that might be possible (Yellow-rumped Warbler and Black-throated Gray Warbler).

I feel a surprising satisfaction from correctly identifying a new bird. It’s a feeling of pride—I did that, I figured it out—and a feeling of learning more about the ecosystem I’m visiting, taking care and interest in my habitat.

If I can’t identify a bird, maybe because it’s too far away or moving too quickly or too nondescript brown, I wonder why it matters to me so much. Surely I can just enjoy the bird without identifying them?

After all, this is an important theme in the way I interact with and understand humans. I shouldn’t need to know someone’s identity to treat them with respect. I may misunderstand someone’s identity at first glance, and I am open to asking to confirm, and being corrected if I get it wrong.

Some people are uncomfortable with gender-nonconforming and trans people because they cannot categorize everyone neatly into the patriarchal, capitalist gender binary. I think that’s a bad trait for humans, something to work on getting over and being willing to expand one’s ideas of who people can be. But what about for birds? Isn’t the need to identify the exact same feeling?

It may be a similar feeling, but with very different consequences. I don’t judge a bird for being a Mountain Chickadee vs. a White-breasted Nuthatch. I’m merely interested in being able to tell the difference. The bird’s job prospects do not depend on my analysis of their appearance. If I get the identification wrong, I am happy to be corrected and feel I’ve learned something.

Also, different types of birds are different species. There is almost no overlap between different species. Bird species are not defined on a spectrum or range of expression. The difference between bird species is easily definable, unlike the differences between most groups of humans. Us humans, after all, are all the same species and share the vast majority of our genetic information: all humans have at least a 99.9% identical genome, with only the remaining 0.1% varying between people.

Learning about the different species in our environment has value, I believe: plants, animals, birds, and mushrooms are all connected in ways we are starting to understand again, as a society.

On a recent hike, sitting on tall rocks watching a huge waterfall, I spotted a gray bird flying out of a crevice in the rock across from us. I could barely see nest material packed into the bottom of the arch and as I watched, two birds entered. There must be multiple birds living in there. One of the birds flew down to the river. I wouldn’t have been able to spot the bird if I didn’t see them fly and land. The bird bobbed rhythmically up and down as they stepped in and out of the rushing water, sticking their head down into the current.

I remembered seeing a similar bird last summer, a dipper. I used the Merlin app to look up the description of American Dipper: “Inhabits only fast-moving rocky streams in the West, from Alaska to Panama…Often nests under bridges.” Well, we were staring at a fast-moving rocky stream, and the natural overhang where the birds were nesting certainly had some characteristics of a bridge. It felt really special to be able to notice and learn about this unique and hard-to-see bird.

In another dispersed campsite, Dave and I were sitting outside the van in our camp chairs when we heard a clear, piercing, two-toned bird call. I got my phone out and started the Sound ID recording. “Western Tanager” popped up. I looked at the thumbnail photo in surprise, a bright yellow bird with a red head. The bird was still calling. We walked up into the pine trees, following the sound.

“Rey! Over there!” Dave spotted the bird first. A brilliantly yellow and red bird was sitting on a pine branch after flying from one tree to another. The bird did not seem overly concerned we were tracking them, sitting thirty feet up in the air. I was amazed at the color. I never would have thought to walk into the trees to look for this bird, if not for the Sound ID.

This morning, waking up in yet another campsite, I heard a chorus of birds calling in the sunshine. The wildflowers right next to our van were beautiful—I hadn’t seen them when we arrived in the dark.

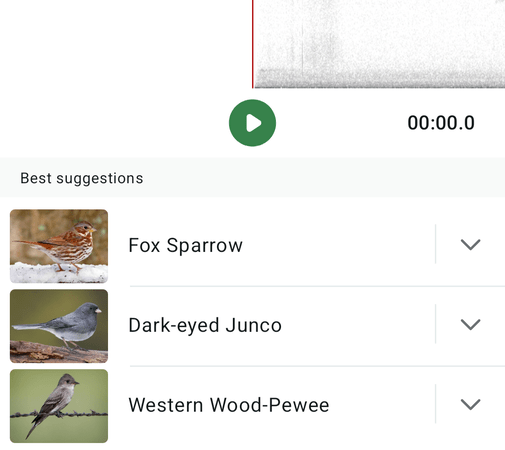

I sat down in my camp chair and turned on Sound ID. No internet, no messages from the outside world, but I was happy to receive the very local info of “Fox Sparrow, Dark-eyed Junco, and Western Wood-Pewee.”

Would you like a supportive, queer-friendly community cheering you on as you write this fall? Please fill out this form if you’d like more info on memoir writing classes and our excellent discussion group:

Thanks so much for reading! Let me know what you think in the comments.

Take care,

Rey

I learned a whole segment on bird ID in a natural history course in college. The teacher was this tiny thing with tremendous energy, and she took us on a 5am nature walk. We listened to the cacophony of birdsong, enraptured but confused. She told us all the names we were hearing. To attract more birds she lifted her hand, curled into a fist, up to her mouth and lightly kissed the side of it to make a sound encouraging the birds. "Like this," she instructed. Joseph, standing right next to her, took her literally. He grabbed her hand and kissed it several times in rapid succession. I wish I could tell you how long the laughter went on (Joseph was a bit of a class clown, obviously), but the birds thought we were too noisy and departed.

I also like the Merlin app. I find it helps me to focus on the moment, by listening to what I can hear, instead of staying in my head.